Recent assessments of the global jihadist milieu have identified the Islamic State’s Khorasan Province (ISKP) as the most concerning Islamic State affiliate for engaging in transnational external operations. It is an extraordinary rise for ISKP given that it was only a few years ago that the group was facing near decimation. Then again, the boom-bust history of the Islamic State movement is filled with examples of seemingly inexplicable rises from the ashes characterised by audacious external operations to not only regain local strongholds, but extend the group’s influence and eventually control into neighbouring provinces and even transnationally. Indeed, external operations are a crucial means by which the Islamic State achieves its strategic objectives, whether ascending or regressing, through the phases of its insurgency campaign.

Typically, scholarship and practice have tended to emphasise ideological compulsion and branding as the key drivers of jihadist external operations. In our view, this captures an important but limited set of explanatory factors. Instead, we argue that the Islamic State’s external operations need to be understood within the context of its approach to insurgency and therefore on a spectrum from local ‘expeditionary’ operations to transnational coordinated and ‘inspired’ operations. To do so we offer a tentative framework for understanding the fundamental drivers of the Islamic State’s external operations. Our argument applies to all provinces within the Islamic State’s global movement, including its prized Khorasan province in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region. We argue that as certain structural and operational thresholds are met, this contributes to the achievement of strategic objectives that help to drive the group through the phases of its insurgency campaign. These dynamics also create opportunities for engagement in different forms of external operations that are deployed to meet ever-changing strategic conditions.

The long jihad: the phases, functions, and thresholds of the Islamic State’s insurgency method

Having analysed Islamic State primary sources – particularly its insurgency doctrine – and examined their operational trends in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Philippines, and the Congo, we hypothesise that broadly similar dynamics drive the Islamic State’s engagement in ‘external operations’, whether into a neighbouring province or transnationally. Namely, certain structural and operational capability thresholds need to be met to enable, and ultimately sustain, engagement in external operations. For the purposes of this study, we apply ‘external operations’ as a broad umbrella term for violent kinetic politico-military operations that seek to extend the reach of an insurgency’s competitive system of control and/or influence over a population. Our focus on kinetic actions implies that this understanding of external operations does not, at least at this stage, include a broad range of top-down political, bottom-up governance, intelligence, propaganda, and other activities. We highlight this while acknowledging that the Islamic State deploys violence in concert with these non-kinetic activities.

Phases

The Islamic State’s method (manhaj) for establishing an Islamic State has at its core an approach to insurgency that all the great architects of modern guerrilla warfare – from Mao and Guevara to Al-Muqrin and Al-Suri – would recognise. The Islamic State’s method of insurgency is characterised by escalating phases of politico-military and propaganda activities as they work to weaken their conventionally stronger adversaries. The phases of its insurgency approach have been defined by the group as (i.) hijrah, (ii.) jama’ah, (iii.) destabilise the taghut, (iv.) tamkin (consolidation), and (v.) khilafah. As the Islamic State seeks to progress through these phases, it is faced with a challenging paradox.

On the one hand, in the early phases of its guerrilla campaign, the Islamic State, as the conventionally weaker actor, cannot allow its stronger adversary to concentrate its focus and resource advantages or it risks being rapidly overwhelmed. On the other hand, the Islamic State is ideologically and strategically compelled to advance through its campaign phases to close that asymmetry gap and extend the reach of its competitive system of control. Despite being materially weaker, the Islamic State insurgency must stretch the adversary but also, therefore, itself in order to drag its opponents through the phases of its insurgency campaign. As the Islamic State progresses, stalls, or regresses through those phases, a spectrum of external operations acts as the mechanism by which the movement seeks to practically extend its sphere of influence, the reach of its system of control, and generate the strategic and territorial depth necessary to reinforce its strongholds. The nature of those external operations will differ depending on the campaign phase that the Islamic State is in and whether it is progressing or regressing through that phase.

Functions

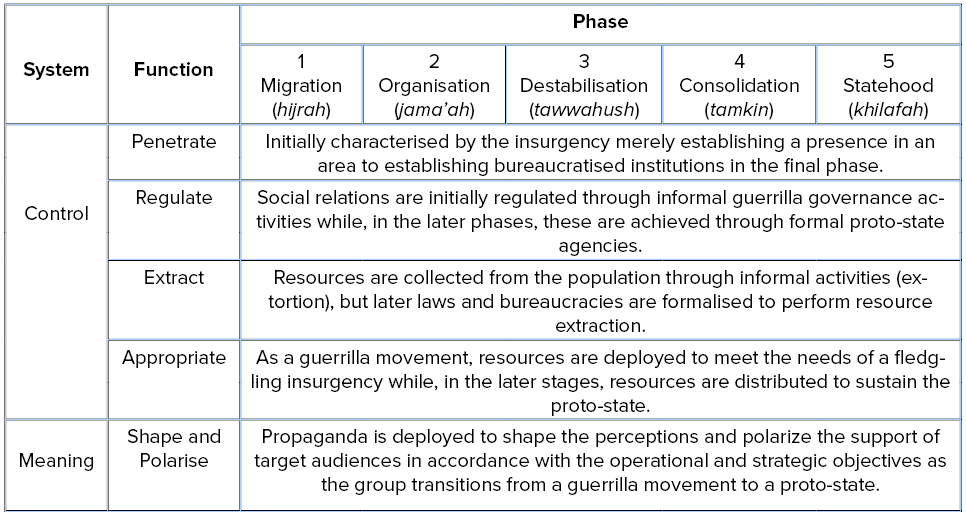

Each of the Islamic State’s insurgency phases has an overarching strategic objective that can only be accomplished by engaging in a variety of politico-military operational activities towards specific functional aims. In many respects, these functional aims are the major grounds of competition between the Islamic State and its adversaries for control of territory, resources, and populations. Four of these functional aims are identified in Migdal’s Strong Societies & Weak States which highlights the capacity to “penetrate society, regulate social relationships, extract resources, and appropriate or use resources in determined ways.” In short, these functions constitute how an insurgency’s system of control outcompetes adversaries. The Islamic State also expends considerable resources on the fifth function in our model: advancing a competitive system of meaning via propaganda activities that shape the perceptions and polarise the support of target populations.

Thresholds

For the Islamic State to engage in external operations, it is necessary for the group to achieve certain thresholds of structural and operational capabilities. Structural capabilities refer to the presence or establishment of human networks into territories and populations in which the Islamic State intends to extend. As it progresses to the later phases of its insurgency, the establishment of organisational structures becomes increasingly important for enabling its external operations. Operational capabilities refer to the expertise and materials necessary to engage in certain kinetic operations. Each phase of its insurgency campaign also constitutes thresholds for structural and operational capabilities that need to be met to enable progression or regression to the next phase.

For instance, and with reference to Table 1, as the Islamic State progresses through the phases of its insurgency campaign it engages in kinetic operations to help create the conditions for it to outcompete adversaries in those five functional battlegrounds. Indeed, the Islamic State will look to engage all five functions in every phase although, inevitably, which are prioritised will depend on operational and strategic factors. Propaganda activities that shape perceptions and polarise support are a particularly important function for amplifying the reach and impact of its external operations. Indeed, without concomitant propaganda capabilities to complement its external operations activities, the Islamic State risks ceding the competition for meaning to its adversaries. In summary, external operations are the mechanism that enable the Islamic State to move through these phases, expand its areas of control and influence, and create the time and space for non-kinetic functions to take hold and vice versa. It is important to now identify the different types of external operations that are deployed to achieve those goals.

Table 1: A Tentative Framework for Understanding the Islamic State’s Insurgency Method through Phases, Functions, and Thresholds

Situating external operations within the framework

Within this framework for understanding the Islamic State’s insurgency method are a spectrum of external operations. This spectrum encompasses a range of operations from local expeditionary operations to transnational expeditionary operations and foreign operations. We define these categories of external operations then explore their application in the case of ISKP.

Local Expeditionary Operations are kinetic operations that seek to extend the Islamic State’s influence and/or the reach of its system of control into new territories and populations at the local level. This spans a potentially broad range of activities from attacks within the same province and into neighbouring provinces. The more sustained the operations, the more likely it is that basic structural requirements, such as the establishment of human networks into those ‘new’ territories, and operational capabilities, such as the necessary expertise and materials, to engage in those attacks, have been met. With time, the recruitment of personnel in those new localities contributes to creating the time and space for functional advancements that lead to those areas becoming new ‘strongholds.’ This may all seem logical and straight forward, but it carries important implications for subsequent categories of external operations.

Transnational Expeditionary Operations refer to Islamic State operations in which the group deploys operatives to engage in kinetic operations in neighbouring countries. The structural requirements tend to be much higher for these operations and include the need for human networks well outside of stronghold regions. This may come in the form of foreign fighters or the international kinship networks of current members that provide opportunities for engagement in transnational expeditionary activities. Transnational expeditionary operations involve expanding the Islamic State’s sphere of influence beyond the boundaries of its declared provinces and other strongholds.

At the farthest end of the spectrum are foreign operations, which can be further divided into coordinated and inspired operations. Coordinated foreign operations involve one or more foreign supporters receiving guidance, instructions, funding, and/or other forms of material support from Islamic State operatives. On the other hand, inspired foreign operations involve one or more followers carrying out attacks in the name of the Islamic State without tangible connections to the movement’s official members based in its provinces.

The rise of Islamic State Khorasan Province’s external operations

Arguably nowhere outside of Iraq and Syria has this spectrum of external operations developed more than in the Islamic State’s Khorasan province (ISKP). Indeed, the group’s early efforts to apply the Islamic State method to the Afghanistan-Pakistan regional environment have enabled ISKP’s resurgence from its early-2020 nadir, leveraging a full spectrum of external operations in the process.

ISKP’s local expeditionary operations during its formative years initially focused on expanding the group’s sphere of influence beyond its core strongholds in Nangarhar province, eastern Afghanistan. Some of its first attacks targeted Kabul and Jalalabad, particularly the ethnic Hazara community in Kabul, as well as various government targets. In turn, these attacks helped to divert the resources of ISKP’s adversaries, create the time and space necessary to both generate support and relieve pressure on its local strongholds, and even reportedly clear routes to allow the entry of foreign fighters into those strongholds. This is a model ISKP has since returned to multiple times, including during its 2020 resurgence campaign and following the Taliban’s brutal crackdown on ISKP affiliates and perceived supporters in Nangarhar in late 2021.

During these formative years, ISKP leveraged transnational expeditionary operations to push outward from the tribal areas in northwest Pakistan and across the country. In short succession from 2015 to 2017, ISKP’s growing network of supporters and alliances unleashed a series of violent operations first in Karachi, Sindh province, then in Lahore and nearby cities of Punjab province, and then most infamously in Quetta, Baluchistan province, along Pakistan’s western border with Afghanistan. More recently, following the Taliban takeover in August 2021, a string of ISKP-coordinated transnational external operations throughout 2022 targeted not just Pakistan in March, but also Uzbekistan in April, Tajikistan in May, and Iran in October. These may seem like the disparate, sporadic attacks of a weak organisation, but they should be seen as a marker of ISKP passing the structural and operational capability thresholds necessary to sustain this yearlong campaign.

Finally, following warnings in early 2019 of ISKP’s foreign operations mandate, proof of the group’s capabilities was revealed in early 2020 with the disruption of an ambitious joint Islamic State-ISKP plot involving four Tajik nationals who planned to target U.S. and NATO military bases in Germany in April 2020. Since then, between 2022 and 2023, reports have surfaced from multiple EU countries detailing ISKP outreach into local communities in Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands to coordinate foreign operations. This while ISKP media output has exploded from less than a handful of regional languages prior to 2020 to over a dozen languages since 2020. Most notable was the launch in January 2022 of its flagship English-language magazine, Voice of Khorasan. Voice of Khorasan frequently eulogises foreign fighter martyrs from operations current and past, has now run multiple articles by purported Italian and Canadian ISKP supporters, and regularly releases commentary inciting violence in response to current events like the Qur’an burnings in Sweden, with some limited success reported in Turkey.

In short, ISKP external operations have expanded since the group’s official formation in 2015 into a full spectrum of operations today, from local expeditionary to foreign coordinated and inspired operations. At the same time, its media activities have rapidly expanded to help amplify and sustain those operations. While some analysts and officials might point to the current lull in overall ISKP operations as an indicator of weakness, the upward and outward trajectory of the group over time is clear.

Conclusion

The example of ISKP practically highlights the role of external operations in the cycles of the Islamic State insurgency. When enemy resources coalesce into a sustained campaign against its networks, the movement’s provinces draw strength from external operations, whether local, transnational, or foreign. Which external operation types are deployed might simply be a function of the operational and structural conditions that exist to support those external operations. Nonetheless, they allow the insurgency to generate strength through other channels when enemy resources are deployed in overwhelming force against local positions and strongholds.

That ISKP today can prosecute an external operations campaign involving all three types of external operations as defined in this paper should be cause for serious concern, even despite temporary operational lulls. It also highlights the broader implications of this analaysies for both scholars and practitioners.

This article tentatively offers a framework through which scholars and practitioners can monitor and track external operations. In doing so, it offers practitioners a mechanism to identify when structural and operational thresholds may indicate that a group poses an increased threat or risk. While this paper focused on the Islamic State, the framework is potentially applicable to other groups with similar ideological and strategic intents. Hamas’ 7 October attacks on Israel highlight the importance of revisiting our understanding of external operations and the need for renewed risk and threat mechanisms.

This publication represents the views of the author(s) solely. ICCT is an independent foundation, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy unless clearly stated otherwise.

Photocredit: Orlok/Shutterstock